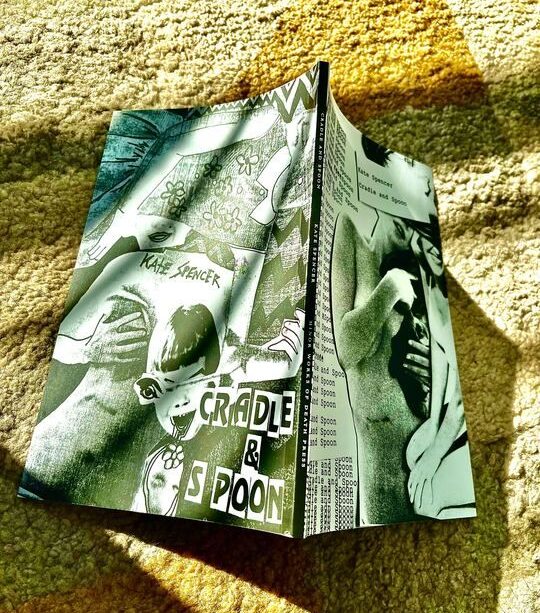

Cradle and Spoon packs a unique punch

A poetry book that I’ll need a while longer to fully finish digesting

While I normally read books front-to-back and then put them down for a while, the poetry book Cradle and Spoon by Kate Spencer demanded more from me. I swept through it – in varying orders – three times in two days.

There are three chapters of poems in this book, ending with an appendix (more of an essay, really). In this appendix, Spencer outlines the inspiration taken from confessional poets who “believed that their art should engage not only with their own, often troubled, psyches but also with their historical moment.”

Spencer expands later that this collection “aims to respond to confessional poetics – affect, pathology, and the body – but the collection is also conscious of postmodernism, how it shapes interpretation, and most significantly, Julia Kristeva’s theories that build on Freud’s work.” While Spencer appears to have placed more weight on Kristeva’s writings, a Freudian tone is evident through the poems and blindly obvious in the appendix.

Spencer states the collection is an exploration of mood, specifically melancholia, which is done through toying with combinations of the symbolic and the semiotic. The symbolic, associated with masculinity in this work, represents form without meaning when separated from femininity. The semiotic, associated with femininity, represents meaning without form when separated from the masculine.

Throughout Cradle and Spoon, Spencer uses fixed form structures frequently, sprinkling in some well executed glosa throughout, but also includes lyrical and prose writing. This breadth of style adds depth to the intimate confessional element of the poetry, equipping the reader with multiple lenses to witness through. Given the focus on moods and pathology, this structure also humanizes the speaker uniquely.

A story and its characters can easily be stripped of humanity once the story is reduced to what can be relayed by ink on a page. A poet holds their own story as semiotic, and must find a way to relay what they experience to others using the symbolic: letters used to form written word. This sharing of accounts immediately shaves countless details from the true semiotic nature of the idea, but without this adaptation the idea cannot be passed.

Spencer’s choice to adapt experiences with so many methods under the same cover makes it more difficult for the stories inside to become dehumanized because it challenges the idea that a person can be understood through one lens, one symbol, one confession. Multiple adaptations of the idea are always required, and even then, you’ll only ever get part of the picture.

Symbols are objects used to represent ideas, so it follows that symbols can be objectified and stripped of their humanity. Cradle and Spoon resists this deprivation because throughout the collection the reader is kept uncertain of the object. Our human impulse to take in information and sort it into clean-cut categories is challenged because nothing occurs in isolation.

I do have one grammar complaint I’d like to make among all this praise. Normally, I like to read poetry out loud, at least the first time I’m going through a new book, but in several poems the comma splices meant I’d have to read the same three lines three times to understand where the story was headed. There is an example of this in “Blood Sister,” a poem where the speaker reflects on joyful memories made with someone dear in the midst of life’s low points. Here is the second and final stanza:

“Begin again, nothing new, cold

coffee and the slight fever reminder: its getting worse, the lack

is hungrier, but your brown skin, in humbling memory, sends

rekindled reason to my feet, and I meet each breath, less

depressed, alive because you

loved me all those years ago.”

The sentiment in this passage is stunning and it calls back to themes from poems earlier in the collection, but I had to read through several times to pick up on that because the form interrupted me. Ironically, as I write this, I realize that Spencer could have done this intentionally, choosing to engage with the symbolic as form without meaning.

Reviewing bittersweet memories is an experience with much emotional range, and sometimes in a processing period you can recognize the event – what it is that actually happened – without being able to unpack the meaning just yet. It’ll keep popping up and you’ll keep turning it over until one day the right approach hits, and the event “nothing new” begins again.

I would wholeheartedly recommend reading through Cradle and Spoon whenever you find the time. Moreover, I would recommend you claim Spencer’s ability to humanize accounts, that you begin to recognize what appears to be a symbol is only ever one facet of the full thing.