Looking through the lenses

Ken Coates speaks about elite students and the need for liberal arts

Ken Coates speaks about elite students and the need for liberal arts

Taouba Khelifa

News Editor

With talks amongst faculty and students continuing around the possible changes that the University of Regina may experience in the next few years, many are concerned with what the future may hold for the liberal arts.

The University of Regina is an institution with a very strong basis in liberal arts education since its inception in 1909. At that time, the University offered academic courses alongside a compulsory course titled “Human Relations” that encouraged students to understand the rising social issues of their era, and take responsibility for making their society a better place. Putting the University’s motto of “as one who serves” into practice, the U of R’s roots in liberal arts continued to grow into the Wascana campus Regina sees today.

However, with the global economic shift in employment, many fear that liberal arts may no longer be seen as necessary in today’s thriving society. With higher demands for practical skills in the job market, liberal arts education has been marginalized and deemed unimportant for the world’s economy. This, argues Dr. Ken Coates, a professor and Canadian Research Chair in Regional Innovation at the Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy, is the painful reality. But, he said, the problem lies not in liberal arts, but in the unmotivated generation of young people today.

In an effort to create more dialogue and discussion around the changes that the Academic Program Review may bring to the U of R, Coates was invited to speak to the University community about the future of the liberal arts, both in Canada and globally, on Thursday Jan. 17.

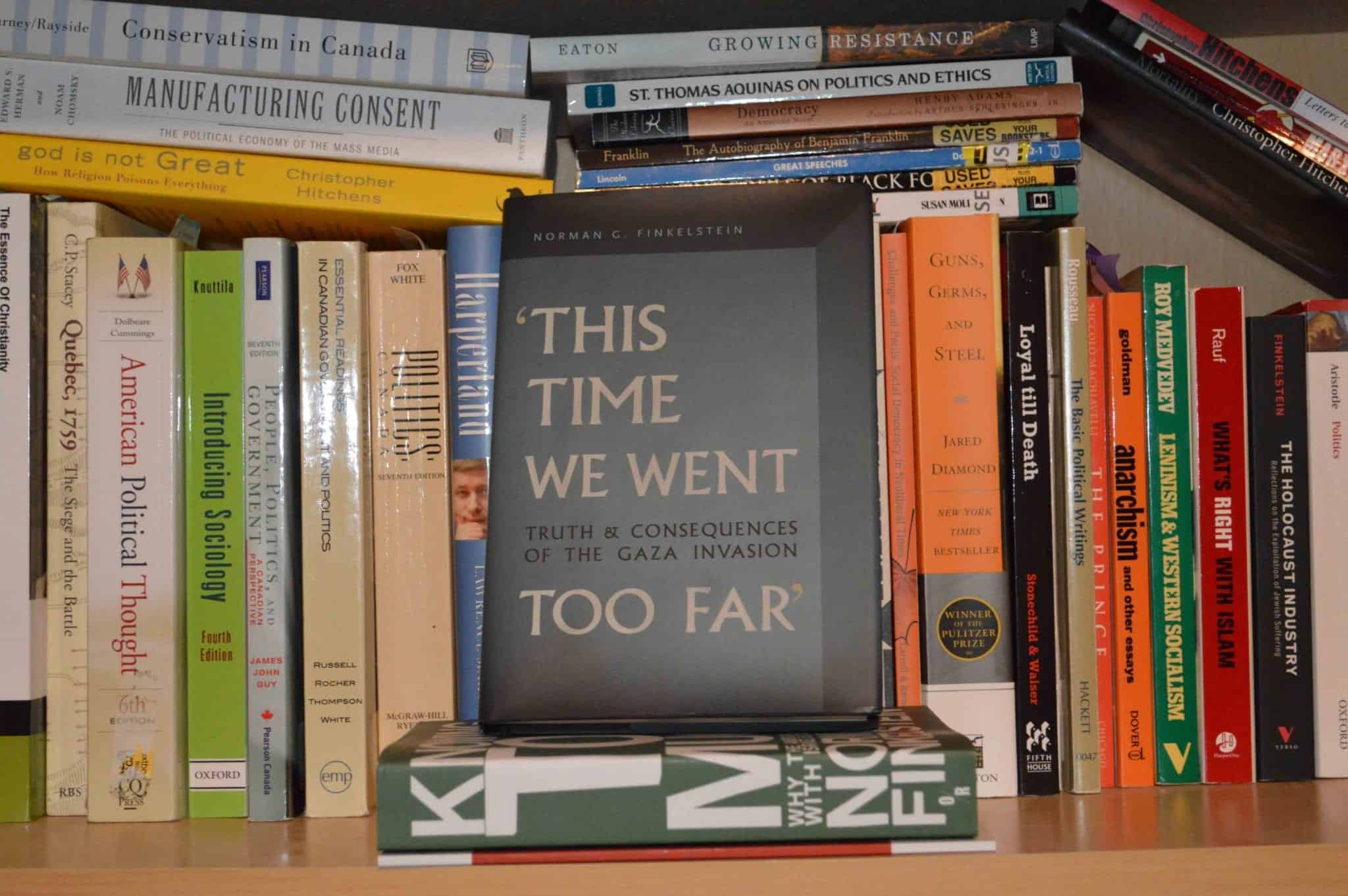

In an analogy, Coates described liberal arts education as sitting in an optometrist’s chair, facing the large ocular device. As the doctor clicks between different lenses, the patient’s vision is cleared or obscured – each lens showing things in a different way. This, says Coates, is the epitome of a liberal arts education.

“Every single click [is] a university class – every one of those clicks either make the world clearer or muddier,” he said. “That’s what the humanities, and social sciences, and fine arts do. They actually take a muddled, confusing world that you see … and through these classes, and courses and experiences, you start to develop for yourself a way to explain and understand the world.”

Beyond just developing well-rounded and engaged students, Coates cites that it was the liberal arts that drove the biggest social movements and changes of our time – from analyzing anti-colonialism and environmentalism, to demanding rights for women, the Indigenous population, and the LGBTQ community. At the core of each of these movements and societal changes, said Coates, is the “spirit and vitality of the liberal arts.”

“Every single click [is] a university class – every one of those clicks either make the world clearer or muddier…That’s what the humanities, and social sciences, and fine arts do. They actually take a muddled, confusing world that you see…and through these classes, and courses and experiences, you start to develop for yourself a way to explain and understand the world.” – Dr. Ken Coates

Despite its importance, the changing dynamics of today’s world have meant a change in how liberal arts education is perceived socially. No longer is liberal arts seen as a prestigious area of study, argued Coates. Rather, with governments pushing for a mass education system where university is widely accessible to any Canadian, liberal arts has become a default area of study for those who cannot succeed elsewhere.

“Governments picked up on the fact that accessibility was the number one political priority,” Coates said. “Governments very rarely talk about high quality university. They like to see universities do well in the grading rating systems, but they don’t really talk too much about making sure that there are places accessible to talented students, they want places accessible to all students.”

This, according to Coates, is the problem. With mass education came a shift in the rational of why students wanted to go to university.

Studies done in the 1960s and 1970s show that students “wanted to learn about the world, that they wanted to discover themselves, they wanted to learn how society operated, they wanted to make the world a better place,” said Coates. Now, he says, students “want money. They learn to earn.”

Coates message centred around a shift in student rationale, coupled with the government push for mass education, which he believes created a society where young people are no longer motivated, engaged, or willing to work. Instead, universities have become institutions filled with students who are disengaged in classes, have little work ethic, and care very little about actually succeeding.

“We have a problem with the current generation of young people … they’re the most spoiled generation in human history. And guess what? They come out of a system where they’ve been told how wonderful they are,” said Coates. “Modern parenting is about telling kids [that they’re] wonderful. Doesn’t work so well with Asian Canadians – their parents drive them pretty hard – but generally [young people] are told how wonderful they are, how terrific they are. Their high school teachers are told to do that, so high school is all about re-affirmation.”

While there are “brilliant students” in university they are often lost amidst the other students who are “coming in for economic reasons,” he said.

Needless to say, it is important to open the doors of opportunity to students, especially those who may be marginalized, but Coates argues that it is naive for educational institutions to enroll so many students, without ensuring that the economy can provide jobs for them once they graduate.

“[The] spread of mass education was tied to, I think, a misapprehension,” he said. “We are overproducing the number of graduates for the economy we have … When I hear Obama saying he wants 80 per cent of all high school graduates to go to university, he is out of his mind. This is a naive assumption about what the relationship between the economy and the university system is.”

According to a study done by the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada, over the past 30 years, the number of university students in Canada has more than doubled. In 2010 alone, there were nearly 1.2 million students enrolled in Canadian campuses across the country, with the number growing every year. While many see this as a positive sign of the country’s growth, Coates argues that universities are simply letting in too many students that should not be there.

“If you want my honest opinion, I think we have way too many students at university, we don’t expect the students to be prepared sufficiently before they come, and we don’t demand of them a really high work ethic. I think we’ve made it too easy to get in, and now we’re trying to make it too easy to get out.”

While many Canadian academics do not share Coates’ sentiments, arguing that this kind of ideology underestimates student ability and devalues student intelligence, Coates said that this change, and this conversation is one that Canadians are not “prepared to have” as of yet.

When the country is prepared to have the conversation, however, he believes he has the solution that can bring back the prestige and importance of liberal arts education in the academic sphere.

His advice: universities must be multi-tiered, offering elite liberal arts programs for curious and motivated students, while allowing economically driven students to take the practical and vocational classes they require to graduate.

“We have to embrace the idea that there are intellectually elite students and they deserve intellectually elite programs. At the same time, we have to realize…[that a lot of students are here] because their parents told them to come, governments said they should do it, and [they] want to get ready for a career. We should not put those students in exactly the same programs and exactly the same classes as students who are basically bursting with curiosity and zeal for learning.”

Photo courtesy of nationaltreasure.wikia.com