Review: Dissident Knowledge

author: john loeppky | editor-in-chief

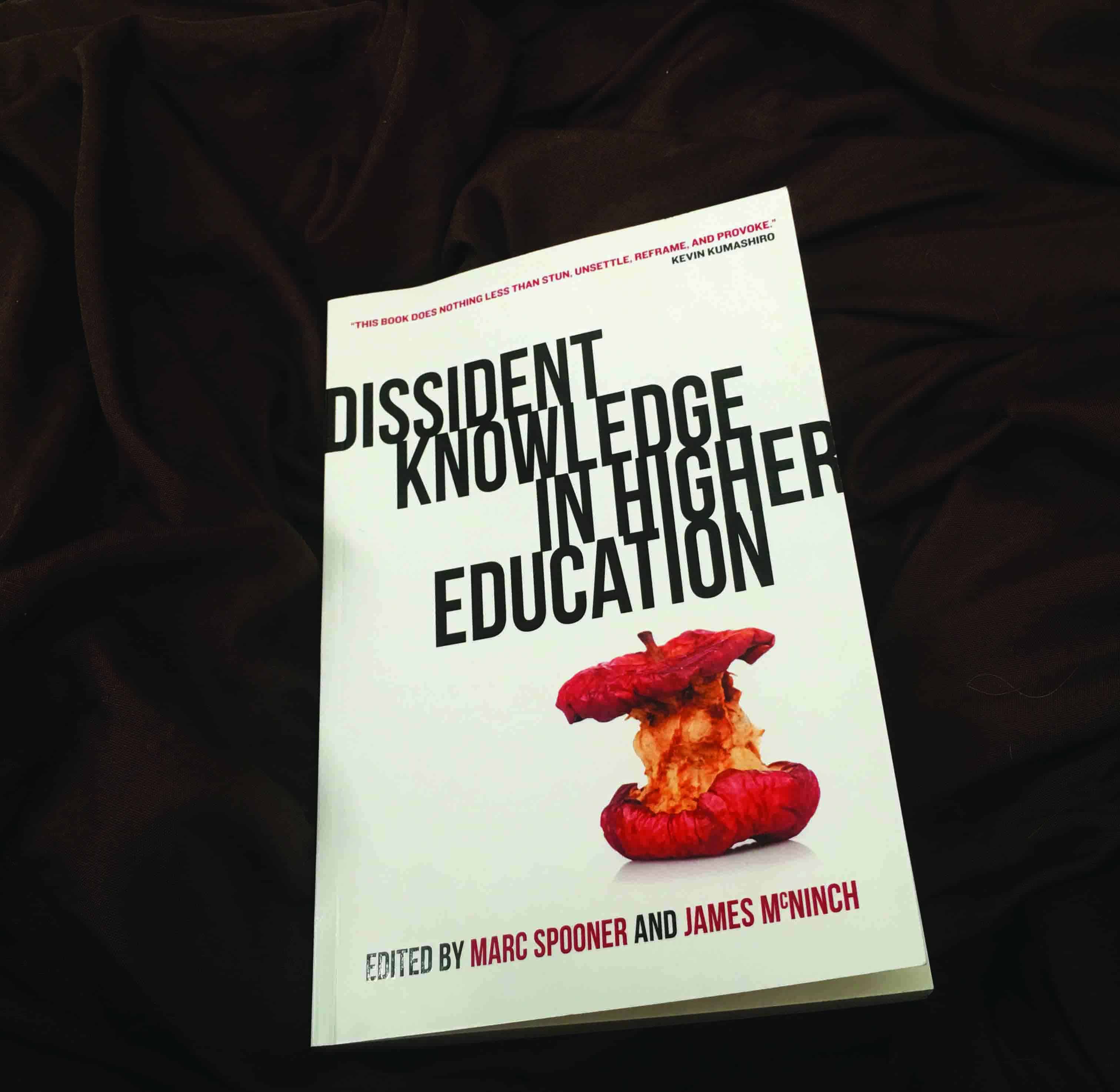

Two U of R faculty release award-nominated book

Dr. James McNinch and Dr. Marc Spooner, both professors of education have released a book that has been nominated for a Saskatchewan Book Award. The text, entitled, Dissident Knowledge in Higher Education, is not one to be taken lightly, even at first glance.

The introduction, sounding more Billy Mays sales pitch than academic snooze fest (and yes, that’s my attempt at a compliment), acknowledges the needs of the reader immediately.

“If you are experiencing a reflexive unease, sensing that something is awry in the academy, then this book is for you.”

While the book is quite obviously aimed at academics feeling the strain of a world in turmoil (see URFA v. University of Regina) there are a number of insights applicable to us lowly students.

For one, the book reads as a roster of heavy hitting academics and critics – for one, is any collection challenging the academy’s structure complete without Chomsky? Obviously not. More than a collection rooted, as it is, in a conference held in 2015 at the University of Regina, Dissident Knowledge comes at a vital time for those both in and out of the academy’s good books. From a review perspective, I think it’s important to mention the background of the two editors, both well entrenched academics willing to stick their proverbial necks out. Now, more than (perhaps) ever, the voices of those able to speak up is vitally important.

Right, on to the book itself. In the first chapter Dr. Yvonna S. Lincoln contextualizes the challenges faced by professors, stained as they are by neoliberalism and what the writer calls “…the more insidious ways in which universities are corporatizing their goals and aims under a neoliberal or ordoliberal regime…” If that doesn’t sound like a sweeping endorsement of higher education, it’s because it, well, isn’t. Paying attention to the structure of any book of this nature, the ways in which Lincoln lays out the battleground on which the text is going to stake its claim is particularly important.

One recent critique I’ve seen of Indigenous acknowledgement is that they do little more than lip service to those reading them. The opposite is true of this volume; it explicitly makes space for Dr. Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s, “The Art of the Impossible – Defining and Measuring Indigenous Research?” which echoes Lincoln’s unease when it comes to the capitalist model of assessing higher education while discussing the different ways Indigenous research (and its impact) can be understood in a contemporary academic context. Her writing on New Zealand’s research climate, and its relation to Maori knowledge, is a refreshing shift from the usual white stuffiness of writing of this type, something that this text does away with almost entirely.

Dissident Knowledge’s ability to fill gaps without self-aggrandizing for its own inclusiveness is one of its best traits as a text. This is second only to the editors’ obvious care in making sure that the thing remains readable. This is not an academic book best served as a doorstop, which having been an education student for much of my academic career, remains a level of high praise for scholars in the area.

Dr. Patti Lather, perhaps best encapsulates the volume with the conclusion to their essay, “Qualitative Research in the Afterward.”

“In all of this, the institutions of higher education in which we function serve as both the harbour and tyrant. What is the cost of the triumph of the mercantilist university?“

This book, it seems to me, is writing exactly about that cost. When the amount of energy used to maintain one’s academic way of life is equal to or more than what is being used on important research, how much does that harm both the academy and the world at large?

It is impossible to fully encapsulate the depth of Dissident Knowledge, but I think the titles of the essays involved give all the clues the lay reader may need. Take, for example, Dr. Eve Tuck’s “Biting the University That Feeds Us.” No hiding, there. Tuck’s conclusion hints at a continual want for more from the academic world in general.

“Lately, I have begun to keep a list of theories of change in my cellphone so I can remember something more meaningful than raising awareness. Something more material than raising consciousness. Something more to the touch than visibility. My list of compelling theories of change: haunting, billboards, visitations, Maroon societies, decolonization, revenge, mattering.”

It’s this boots on the ground approach that elevates Dissident Knowledge as both a readable and, more importantly, actionable text. It is available from the publisher, the University of Regina Press.