Truth and reconciliation: when is the time?

author: alyssa prudat | contributor

jeremy davis

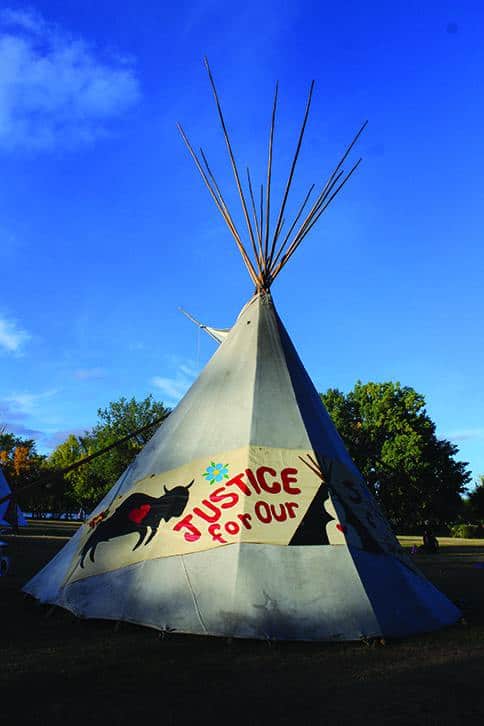

After nearly 200 days, Camp No Justice for our Stolen Children is given a court order to dismantle their peaceful protest

Sept. 9: “O Canada,” sung in an Indigenous language, greets the runners of the 2018 Queen City Marathon. A speaker acknowledges that our course is on Treaty 4 Territory and the land of the Métis people. A finishers’ medal comes adorned with the beautiful image of First Nations University. When I pass the Legislative building, I see the camp and I know that there is a court-ordered removal of the teepees. There is silence when we pass.

After nearly 200 days, Camp No Justice for our Stolen Children is given a court order to dismantle their peaceful protest. The court says that the camp is in violation of laws against erecting campfires and structures in Wascana Park. These actions of truth and reconciliation are performed to say that we are making a change – but what change are we actually putting effort into making? When is a convenient time for truth and reconciliation? Ironically, in the same month as the dismantling of the camp, public schools will be honoring ‘Orange Shirt Day’ on September 28 – a day dedicated to the truth of residential schools and its violence against Indigenous children.

We are ready to speak about the injustices and failure of the courts in both cases of Tina Fontaine and Colten Boushie. We are ready to speak of missing and murdered Indigenous women and issues of pipelines, housing, and poverty that First Nations communities face. As early as September 12, 2018, First Nation leaders met with Justin Trudeau, and he remarked “I am really upset,” when there were too many voices to be heard and too little planned time. Even earlier than that, his visit to Regina for the 2018 Canada Day celebrations did not include a visit to Camp No Justice.

So, in an organized meeting, there is no convenient time for truth and reconciliation. The nearly 200 days of a peaceful protest is not a convenient time for truth and reconciliation. As I write this, another assailant of another Indigenous woman has been let off (Sept. 22) with no prison sentence, despite pleading guilty to dehumanizing violence and sexual assault. Justin Schneider’s victim lived. Tina Fontaine did not. Buried in a blanket, she is another one of our missing and murdered Indigenous women that Canada cannot find a convenient time for.

Observing these cases, the court system is in favor of white cisgender men. It is our courts’ failure that allowed an all-white jury to convene in North Battleford to determine if a white farmer is guilty of murder – North Battleford, the 1885 site of a mass hanging of Indigenous people. The color of Indigenous people’s skin is seen as a determining factor that makes them too biased to be on a jury. And yet, those white faces that benefit from an environment of systemic racism are not seen as too biased to be on a jury. The experiences of Indigenous people are not seen as a determining factor of knowledge; the knowledge behind understanding reservation life is not seen as a strength.

The thing about protests that have made changes in the world is that the system that these people are protesting is the same system that allows a protest (i.e. by way of a park permit). The first Pride was a riot. The civil rights movement was breaking laws by forcing those who benefit from systemic racism to listen. So, “Why did the camp not apply for a permit?” What people who make this argument fail to realize is that the camp is damned if they do and damned if they don’t. They will be denied a space to peacefully protest just as they will be blamed for not applying in the first place. Earlier this year, police had attempted to take down the camp. Dubois’ powerful voice was not silenced, neither were the other protestors. The fact is that Camp No Justice was attempting to tackle a system of injustice that is unwilling to change from what is comfortable. Laws are not changed until they are challenged. As time continues, these laws will continue to be challenged until justice is found.

This argument of a park permit also distracts from what Camp No Justice for our Stolen Children is trying to say by maintaining a presence in front of the Legislative building. No more do we want to watch our children disappear and watch their murderers and assailants walk free. No more do we watch trials atop the dead of ancestors killed. Camp No Justice for our Stolen Children shows why Truth & Reconciliation is so necessary. Without education of our court systems and how the justice system of Canada works against Indigenous peoples, we cannot keep the cases of Tina Fontaine or Colten Boushie from recurring.

Next time, as there will unfortunately be a next time, it is everyone’s duty to educate themselves on the law and how that system failed people like Tina Fontaine and Colten Boushie. As a Mètis woman, I do not speak on behalf of all those defined by Canada as Aboriginal, but I do ask again: when is a convenient time for Truth & Reconciliation? The idea that Indigenous people are responsible for educating against racism is a colonialist one. On the cases of Tina Fontaine, Colten Boushie, and countless MMIW & children: people have the duty to educate themselves on this. It is much too easy to walk past the teepees outside the Legislative building during Canada Day celebrations and pretend that it is not happening. It is much too easy to walk past the teepees outside of First Nations University and ignore the beautiful works of art that showcase colonialism, culture, and thousands of years of tradition. The real truth is that we all must educate each other and be willing to listen when peaceful protesters demand to be heard. There is no point in a meeting if people refuse to hear before it begins.